Paul Prichard ’60 stepped out into an uncertain world. It was late spring 1960, the Eisenhower era was coming to an end, and the nation was sliding into an economic recession. Jobs were scarce for young Chapman grads like Prichard, and he didn’t really know what he wanted to do anyway. Business of some sort, for sure, but what?

Prichard ’60 had already worked briefly for a savings and loan in Santa Ana, so he decided to try banking for a while. It was the proximity it offered to other options that drew him. He figured as a banker he’d meet a crosssection of business movers-and-shakers, and amid all that elbow-rubbing he could decide where to build his career.

Prichard was lucky. Despite the tight job market, with his experience and a fresh bachelor’s degree in economics and business he was able to land a spot in a Union Bank management-training program in Los Angeles. But his elbowrubbing plan didn’t quite work out the way he anticipated. A half-century later, Prichard is still in banking, now as a vice president for Pacific Western Bank in Anaheim, in a career that has been remarkably stable even as the work world around him has changed in radical ways.

“It was eight-hour days, a downtown operation,” Prichard says of that first job, which came with a full roster of health coverage, a retirement program and a support staff. “Today, you’re pumping your own gas. There’s no personal assistant and so forth, like in the old days. ‘Here’s a computer, you do your own letters and spread sheets. … You come in early and stay late.’ The hours are not 8 to 5.”

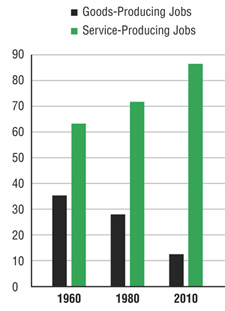

In this era of instant communication — and instant gratification — it can be hard to see broader and more glacial changes in the way we live. Yet there are few places in American life that have undergone more radical changes than where and how we work, and what that work means to us. These days, fewer of us toil in factories and more of us work from home, often for ourselves either as entrepreneurs or as independent contractors (this article, in fact, was written under a freelance contract by a former newspaper staff writer). That growing class of workers is responsible for its own health coverage and retirement plans, a quantum shift that is changing how we view what we do, our employers — and our perceptions of the importance of work in our daily lives.

“There’s more of a social aspect to life now,” Prichard says. “Back then, we didn’t have a lot of things to think about. You had your family and your job. If you wanted to do well with your job, and progress, the family took a bit less time and effort and energy. Today, it’s the other way around — people are concerned about their social standing and taking care of their family and being more involved in charitable work and church.”

And gone, Prichard says, are the days when workers could feel a sense of security about their jobs. “It’s an at-will thing everywhere now,” he says. “Its not that they can just fire you under any circumstance, but it doesn’t take a lot. If there’s a shortage of work and they have to cut back, there doesn’t seem to be any law or moral issue they have to live up to.”

Work remains a key part of most Americans’ lives, says Joel Kotkin, an urban development expert and Chapman Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures. But where single-wage families formerly were willing to move multiple times following corporate transfers, now families often have two wage-earners and are less likely to sever roots for the sake of a promotion.

Where single-wage families were willing to move multiple times, now families often have two wage-earners and are less likely to sever roots for a promotion, says Joel Kotkin, Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman.

Other factors have gained weight in those family decisions, including quality of schools, the tug of leaving extended families, and concerns over whether the other working adult in the household can find a job in the new location. At the same time, firms looking to cut expenses by consolidating operations are more apt to fire workers in one locale and hire fresh in the new. And that lack of loyalty to employees spawns a reactive lack of loyalty by workers, Kotkin says. Where employees once took pride in their longevity with one employer, these days corporations shed workers — and workers leave employers — in a constant churn of relationships. A generation ago, a worker might define himself by his firm –“I’m a Xerox man.” These days, he or she is more likely to identify first by expertise, and then by employer.

Kotkin believes other factors are at play, too, including the changing nature of family life. A rise in divorce rates has led younger generations — young adults often raised in broken homes — to put more emphasis on their family life, hoping to avoid what they see as two great failures of the generation before: Fractured families, and misplaced loyalty to corporations willing to jettison workers.

“It started when the (baby) boomers were watching their own fathers work for 40 years for a company, and get laid off,” Kotkin says. “This impacts how people feel about work. They realize there is no loyalty.”

He believes the attrition in white-collar jobs, which followed the effective collapse of the nation’s heavy-manufacturing industry, has had a critical effect on the nature of work — and, by extension, corporate health.

“If you take a look at Silicon Valley, they started losing manufacturing to the Far East and to other parts of the country,” Kotkin says, sipping coffee outside Jazzman’s Café on the Chapman campus. “Now we’re seeing the research and development jobs and the software jobs going. The very top jobs are still there, and the younger entrylevel jobs are still there. But everything else is being hollowed out.”

He lays the genesis of that change to the rise in influence by the financial world, from Wall Street down to the corporate decision-makers pursuing short-term profits ahead of long-term stability and, in the case of laying off large chunks of their work force, failing to maintain a “farm system” of leaders to serve as future leaders of the corporation.

“A lot of people in the financial world don’t consider these kinds of things as being remotely important,” Kotkin says. “What’s happened in the last 30 years is the financial sector has become more and more important. They began to define the values of work life, and they have a very ‘winner take all’ view. They don’t care really what happens to the product as long as it’s making a huge profit.”

For recent grads, the working world is “a Sahara,” Kotkin says. “There is so little out there.”

But changes in the nature of work aren’t new, says Paul Apodaca, Ph.D., associate professor of sociology at Chapman.

“The cycles of economy and technology produce similar situations over time so that the discussion of how technology is affecting work occurs in every age among all people but always seems urgently new to those looking at the issue,” Apodaca says. “It is somewhat illusionary to think the changes we are going through at any particular moment are more important or consequential than those experienced by folks in the past or in the future.”

And what doesn’t change, he says, “is who is going to do the work and that work will define roles in culture and society.”

Yet Kerk F. Kee, Ph.D., assistant professor of communication studies at Chapman, thinks the rise of independent contractors instead of full-time employees could be read as an emancipation of workers from their employers, a further collapse of the bonds that arose during the industrial revolution.

“The contractor’s arrangement allows today’s workers to maintain a sense of control over their own time and personal priority while keeping companies as sources of income and livelihood,” he says. “Perhaps some workers may begin to see another layer of reality. While they may identify themselves with the corporations they work for, the corporations may not completely identify with, or feel tied to, or dependent on, the workers that work for them.”

That feeds into what Dr. Kee sees as a national tendency to individualism. The industrial economy forced individuals to subjugate themselves to their work, from the dehumanizing elements of assembly lines to the expected conformity of corporate culture. The new economy has fewer constraints. “Knowledge and information work has a greater degree of personal flavor to it,” Dr. Kee says. “It is not that workers have changed, but the work environment and the nature of work have changed.”

The newest generation of workers could be in a prime position to achieve more satisfaction from their careers than many in previous generations did.

“Perhaps the seductive idea of being entrepreneurs, coupled with our cultural tendency of individualism, plays a role in giving this generation of workers the vision that they can work for themselves and maintain a sense of autonomy on how they can express their own talents, specialized skills and personal dreams,” Dr. Kee says. “In that sense, contractors have a say on who they are as specialists, and this professional identity helps redefine their relationship with the companies that pay them for their work. The work they perform helps them build their personal career, and not simply a job that pays the bills.”

One of the biggest changes in the work force over the past generation or two has been women expanding and continuing their working lives. It’s not been an easy transition. Women still make less than men, on average, for performing similar work, says Roberta Lessor, Ph.D., a Chapman professor of sociology who studies women in the work force. The gap has narrowed to women making 80 percent of what men make, but it’s still there.

One of the biggest changes in the work force over the past generation or two has been women expanding and continuing their working lives. It’s not been an easy transition. Women still make less than men, on average, for performing similar work, says Roberta Lessor, Ph.D., a Chapman professor of sociology who studies women in the work force. The gap has narrowed to women making 80 percent of what men make, but it’s still there.

“The Women’s Movement of the late 1960s and 1970s marked a change from women constantly moving in and out of the labor force to women being continuously employed,” Lessor says. “Protesting against the then-59-cents-onthe- dollar wage gap with men, women struggled for parity in hiring, promotion and a place at the bargaining table to not only enter but to keep good jobs as they managed family responsibilities at the same time.”

Still, Dr. Lessor says, the future bodes well for women. They account for 58 percent of college enrollments overall, and about half of current enrollments in medical and law schools.

“The gendered change in education will bring great change to the work world as well,” she said. “A new generation of educated women stands to become leaders, at least in new ways of thinking about work.”

At this point, Caroline Stegner would just like to work, period. She graduated from Chapman in May 2010 with a bachelor’s degree in English — emphasis on journalism — and a minor in communications. A Panther newspaper staffer, she landed internships at Modern Luxury magazine and The Orange County Register, and until September was working as an editor’s assistant at Modern Luxury, but that gig dried up.

Stegner wants to work as a newspaper reporter. But as that industry continues to struggle, she’s looking now at pursuing a career in public relations or in some other non-journalistic slice of the mass media industry. But the biggest hurdle she faces in finding a job is her top priority: staying close to her family in Mission Viejo, with whom she still lives. Even moving 50 miles up the I-5 freeway to Los Angeles would take some convincing.

Erik Wright ’08 and Evan Minogue ’08 joked at Chapman about opening a “fantasy bike shop,” and now they’ve made it happen.

And that puts her directly in the realm Kotkin talks about, those who put family concerns ahead of professional ambition. Given a hypothetical option between a newspaper job in New York City or a public relations job in Newport Beach, with salaries offering identical standards of living, Stegner says she’d take the PR job, despite her dream of being a journalist.

“Our family is very close,” Stegner says. “My mom is one of my best friends. We cook together — we do everything together. It would be hard if we lived in different states.”

Two 2008 Chapman graduates decided to try to create their own luck. Erik Wright, from Seattle, was a political science major and volunteered for the Obama campaign before taking a job with a legal-aid organization in his hometown. Evan Minogue, of Los Angeles, was a film major “and got burnt out, and we said, dang, what can we do now?” The two friends had joked in college about opening a “fantasy bike shop,” and decided to try to make the fantasy a reality.

Minogue’s family has a home in Carpenteria, and initially they scouted shop locations there before deciding Santa Barbara made more sense, in part because of the bigger potential customer base. They zeroed in on a niche: heavy-duty commuter and cargo bikes that they thought would draw attention in the bike-friendly city. With financial backing from Minogue’s family, they opened the doors to WheelHouse Bikes in May 2009 — a year after graduating.

So far, Wright says, sales for 2010 are well ahead of 2009. Growing too is their sense of satisfaction with their work lives.

“It’s definitely not the easiest thing in the world,” Wright says, “but it’s a whole lot of fun every day.”

Scott Martelle, an instructor in Chapman’s journalism program, is an Irvine-based author and journalist.

Leave a comment